- Forgotten Lives of Oxfordshire

- Posts

- Workhouse eye-witness

Workhouse eye-witness

by Julie Ann Godson

The workhouse in Hensington Road, Woodstock

Joseph Oliver of Stonesfield near Woodstock gives us a first-hand account of life in a Victorian workhouse in the 1860s. Although Oliver was perfectly literate thanks, he says, to a good education at the village school as a boy,1 due to his failing eyesight his words were taken down by workhouse chaplain the Revd W. Saunders.2 Probably what brought Oliver to Saunders' particular notice was his participation in the battle of Waterloo; in a precursor of our own late twentieth-century realisation that the small group of survivors of the First World War was dwindling, there was an upturn in interest in veterans of the final battle against Napoleon. Saunders explains frankly in Charles Dickens' periodical All Around the Year that, 'The following memoir was not actually written down on paper with pen and ink by the narrator himself, but it is a transcript of notes made during the old man's narration, and is in truth what it professes to be: the real, uninterpolated history of a genuine soldier of 18th June 1815, given as nearly as possible in the veteran's own vernacular.'3 Oliver's military memoir is published elsewhere4 and, happily for Oxfordshire historians, his original narration of that story to Saunders also included the details of day-to-day life in the Woodstock Union workhouse.5

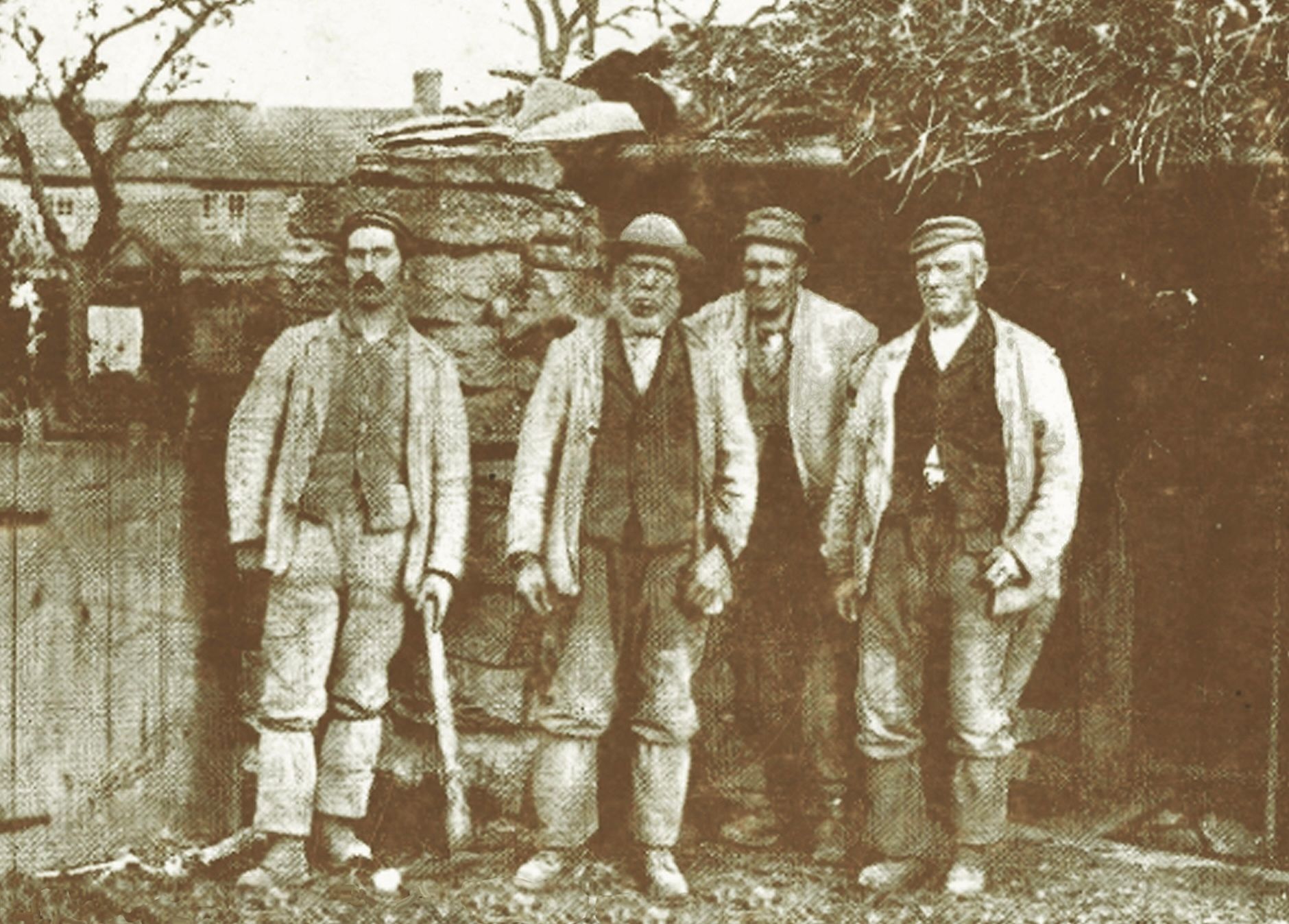

“Slatters”: workers in the Stonesfield slate industry

Joseph Oliver was born in Stonesfield in 1792.6 Like most of the menfolk in the village, the Oliver men worked in the local hillside quarries. Stonesfield slate was reputedly the best, lightest and least porous of roofing materials. The slates, created by the splitting action of frost on fissile rock, were in use by the 17th century, at a time when there was rapid building development in the region.7

At nineteen, and somewhat harassed by the family of the young woman he was courting,8 Oliver went into Oxford to sign up with the local militia and then transferred to the Rifles. This put him at the heart of the action at Waterloo, the highlight of his military career, but he had no wish to remain a soldier.

‘I was anxious to get home,' he revealed, 'and, as I was only 'listed for seven years, my time – allowing for the two years given us for Waterloo9 – was up on 13 November [1818]. I then received my discharge. The colonel, Colonel Duffy10 , and the sergeant-major, both wished me to stop, although I was half an inch under the standard [height]. But I felt drawed home and so I left, with a good character… in the middle of November.

‘I wasn't entitled to any pension because I only 'listed for seven year, and wasn't lucky enough to get a scratch of any kind. Our passage was paid to Bristol, and I reached home early in December after having been away more than seven years.’

Oliver returned to the shattering news that his sweetheart had died a few months before. He went back to work in the slate quarries of Stonesfield.11 ‘I was now twenty-six year old. My gran'father had a slate-quarry.12 I worked for him for five years, when he became bed-ridden, and soon afterwards died. After that I worked for one man seventeen years, and then another for eleven years more.

‘I married in 1824. We had six children; three are alive now, two sons and a daughter, but where they are I don't know. I haven't seen or heard of my sons for years.13 In 1841 I lost my sight; leastways, lost it so far as I was unable to continue my work. I had been a teacher in the Sunday-school for twelve years, and was obliged to give that up. That was a great grief to me as I used to love to be among the children.

'Two year later I lost my wife,14 and two years further on I lost my eldest daughter. After my wife died, my daughter as is alive now kept my house for ten years, when she was ruined by a young man who had promised to marry her, and got a house ready. She had always been a good girl up till then, but that seemed to throw her quite off her mind, and she didn't seem to care what she did or what became of her. Ever since then she has been a constant grief and trouble to me, and the last I heard of her was that she was in jail for sleeping in a cowhouse.'

Indeed she was. On 3 November of the same year that the above account was first published, 1866, a report appeared in Jackson's Oxford Journal: ‘Sophia Oliver, of no settled place of abode, was charged by the police with wilfully damaging a window at the Witney Police Station. She had been several times before the Court for sleeping in the open air. The prisoner was convicted, when she said that she had been in custody a week, which she considered was sufficient punishment. The Magistrate said that from the fact of her having been there so many times previously, they felt bound to inflict the full penalty, namely a fine of £2, with costs 16 shillings, or two calendar months' hard labour; committed.’ Sophia died in the workhouse at Woodstock in the following year, aged thirty-three.16

Joseph continues: ‘After I lost my sight, I had an allowance from the board [of guardians] – half-a-crown and a loaf a week; but my sight got worse and worse, and I couldn't do anything to earn a trifle and so, as I couldn't live honest out [in the community] on half-a-crown and a loaf a week, I came into the workhouse in 1860.’17

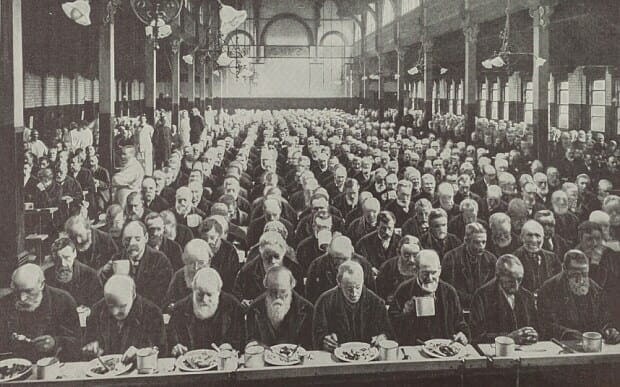

In spite of having seen something of the world as a soldier, Oliver was still disconcerted by the mix of types on display among his fellow inmates. He recalls: ‘When I first came into the Union I was put into the old men's wards. I thought it was a strange place, amongst a parcel of people from all parts. They was then very bad behaved; their conversation was horrid bad, and altogether it was a great trial to me. I don't say they was worse than me, but their conversation was so different to what I had been accustomed to.

‘I used to go down to work in the stone-pit belonging to the workhouse till the doctor ordered me not to go, as my eyes was so bad he was afraid I should fall in. The next year I was put into the men's infirmary, where I was orderly-man for three years and a half. My eyesight then became too bad for me to be of any use much; and I have since been sometimes in the infirmary and sometimes in the old men's wards. In the six years I have been in the house I have seen above thirty deaths I should say, altogether, and always found the dying very grateful for anything I could do for 'em. Many of 'em who used to call me “selfish” have become very friendly before they died.18 In particular, one young man, a cripple, who had always been a great enemy to me, begged me that I would take the sacrament with him before he died.’

Grinding boredom is not, perhaps, an aspect of workhouse life that a modern reader might expect to find mentioned in a memoir. Once inmates were too infirm to carry out useful work, they were simply housed and fed. ‘The worst of the workhouse, especially when there is none of us in the ward as can read (and I can't read now, because of my sight) is that the days are so long and tedious; and the men, having nothing to do, will quarrel and storm so among theirselves about nothing. And it's wonderful how jealous everybody is of everybody else. I may say as envy rolls about in great heaps.’

Even today, patients confined to a hospital bed and compelled to do very little for long periods will confirm that mealtimes take on a disproportionate significance. Oliver describes the workhouse regime in considerable detail: ‘We old folks used to have meat for dinner and tea for supper every day till quite lately; but both meat and tea was taken off from me and thirteen more a few months back, and for some time we only had what is called the “house diet”. But there has been a new order again, and all of us as is over sixty now get our tea, but not the meat every day as we'd used to do.19

Joseph Oliver reveals the truth about workhouse food

‘We now have for breakfast (at half-past six) tea and six ounces of bread; and for supper (at half-past five) we have bread and cheese and tea. For dinner on Sundays and Thursdays, we have soup. I have had a bad rupture (about 1840), and the pea soup don't agree with me. I don't eat a basin of soup once in a month. On Mondays and Fridays we have cold boiled beef and vegetables; and then I can manage to eat enough to keep me going, but my constitution is gone and I haven't any appetite.

'On Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays we have suet pudding. This I can't manage at all; it is too heavy. When I try to eat it, I have a bad pain in less than half an hour. So I generally leave it on the table and anybody has it. I feel I am fast going down hill; but I could eat better and should suffer less pain if I could have something lighter to eat. I don't think I've eat an allowance of cheese for three weeks. If I could but have half a pint of beer a day, it would be everything to me. I could do with that and my bread, and should be contented.

I hope I'm as happy as anybody can be in a workhouse – but I never knowed anybody stop in as could get out. In particular, they are very averse to dying in the house. I recollect one man – a very respectable sort of man he was – saying to me, "If I only knowed the night I was going to die, I'd get over the wall." And he meant it. He never smiled a bit. He was quite serious-like.’

Here Rev Saunders enquired of Oliver whether there was anywhere he could be taken care of in his native village of Stonesfield and, if so, how much it would cost. Oliver confirmed that there were ten or a dozen places he might go for five or six shillings week. Brightening visibly, he cried, ‘Ah, sir! That would be too great happiness. Oh! How glad should I be to have liberty once more! Often and often do I say over to myself the lines (perhaps you may know 'em, sir):

“Eager the soldier meets his desp'rate foe,

“With fierce intent to give the fatal blow.

“The thing he fights for animates his eye,

“Namely, religion and dear liberty.”20

According to Saunders, at this point the light faded from Joseph Oliver's face and he added submissively, 'And I'm a prisoner!'

Moved to action by this state of affairs, the Revd Saunders set about mounting a campaign to bring Oliver home to Stonesfield. According to Jackson's Oxford Journal, Saunders:

… exerted himself on [Oliver's] behalf, both with the War Office and the public generally, with such success that a pension was granted by the former and a subscription obtained from the latter sufficient to purchase an annuity, which enabled the old soldier to retire to his native village and spend the remainder of his days in comparative comfort.21

Indeed, by 1871 Joseph Oliver was listed in the census as living in Stonesfield with a cousin, Robert Oliver, seventy-five, who was still working as a slate maker, and Robert's wife Susan, still a gloveress at sixty-two. Joseph himself is described as a ‘pensioner’ where otherwise he would have been a ‘pauper’. Two years later, Joseph died and was buried in the church of St James the Great in Stonesfield, where this uncomplaining and modest man had been baptised eighty years before.22

We are fortunate in Oxfordshire to have access to the main family research websites at no charge in local libraries; just register online for an Oxfordshire Libraries membership card at www.oxfordshire.gov.uk/oxfordshire-libraries

1 Presumably one of two dame schools established in the village by 1808, see British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol11/pp181-194 [accessed 14 April 2022].

2 In Foster's Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715-1886, there is only the Revd William Sidney Saunders of Derby, Lancashire.

3 'Waterloo and the Workhouse', All Around the Year, 18 August 1866, p. 125.

4 Waterloo Association Journal, July 2022. [Article title and author?]

5 A good summary of the history of Woodstock Union workhouse can be found at https://www.workhouses.org.uk/Woodstock/

6 Oxfordshire Family History Society; Oxford, Oxfordshire, England; Anglican Parish Registers; Reference Number: BOD259_b_1

7 British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol11/pp181-194 [accessed 14 April 2022].

8 Probably Mary Smith, baptised Stonesfield 1794, buried 4 August 1818, daughter of blacksmith John Smith and his wife Mary. (ORO, Parish registers, church of St James the Great, Stonesfield)

9 Two years' service towards their pension were added where the soldier had fought at Waterloo.

10 Presumably ‘J Duffy, Lt Col Rifle Brigade’, author of a testimonial on behalf of Quartermaster Surtees in W. Surtees, Twenty-Five Years in the Rifle Brigade (1833), p. 425

11 According to British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol11/pp181-194 [accessed 14 April 2022]: 'The first deposits to be worked were those in rocky outcrops along the slopes south and west of the village. Later, horizontal shafts were driven and by the late 18th century pit shafts were being sunk, although horizontal galleries were still in use in 1820. Some shafts reached a depth of 65 ft. Between Michaelmas and Christmas the slate diggers produced the raw material for the small number of full-time slate makers working on the surface. The stone was laid out in the fields, wetted, and covered with earth to keep it damp until a frost. The size of the workforce is uncertain, for most diggers spent much of the year as agricultural labourers. In 1801 only 7 slate diggers and 2 slate makers were recorded, but there were 57 unspecified labourers. In 1811 'trade' engaged 51 people, including 22 of those described as labourers in 1801, probably a fairer indication of the number of slate workers. In 1831 there were 20 slate makers and an indeterminate number of diggers, but thereafter the numbers seem to have declined.'

12 Perhaps individual shafts and galleries were let on a concessionary basis, hence Oliver's grandfather 'had' a quarry.

13 According to the UK census, in 1851 elder son Edward was living in Combe with his wife and three children, and working as a slate maker. He disappears from the record after this. According to the census, in 1861 younger son Job was working as a servant at the Marlborough Arms in Charlbury. Later in life he worked as an insurance agent in Stonesfield (UK census 1891: PRO RG12/1173). He died in 1917 aged 74.

14 Ann Oliver, born Ann Davies, married Stonesfield 1834, died giving birth to Job in Stonesfield in 1843: OHC, parish register transcript, Stonesfield).15

15 Elizabeth Oliver, baptised at Stonesfield 1828, died there in 1850; she was twenty-two (OHC, parish register transcript, Stonesfield).

16 (OHC, parish register transcript, Stonesfield).

17 Oliver's inability to pay the poor rate led him to fall foul of the law. A report in Jackson's Oxford Journal on 21 March 1857 reveals that he was in arrears of twelve shillings, three pence and three farthings, which the Overseers ordered him to pay, plus court costs.

18 The Revd Saunders here interjects the explanation that by “selfish” the paupers meant “conceited”, “stuck-up”, “self-righteous”. As a disciplined and literate man-of-the-world, Oliver was probably an exotic creature in the workhouse.

19 In the absence of any obvious new legislation in the 1860s, the new order of which Oliver speaks may have been instigated locally and enacted by workhouse Master, James Otway. Having for eighteen years been porter at Blenheim Palace, Otway was elected to the position in 1858 and remained there until his death in 1875 (Jackson's Oxford Journal, 11 December 1875).

20 T Dilworth, A new guide to the English tongue, 1818, 'On the soldier', p. 141. Dilworth, a schoolmaster at Wapping School in the eighteenth century, produced his guide to assist teachers in the classroom. With a good education himself, and a need for materials as a Sunday-school teacher, Oliver will have been familiar with Dilworth's works.

21 Jackson's Oxford Journal, 'Death of a Waterloo Veteran', 16 August 1873.

22 OHC, parish register transcript, Stonesfield.