- Forgotten Lives of Oxfordshire

- Posts

- The squire, the cook, their daughter, and the Duke: part 1

The squire, the cook, their daughter, and the Duke: part 1

The Cook's Tale

Sophia Wykham of Thame Park (1790–1870), was widely regarded by those who knew her as a remarkable woman. She inherited Thame Park at the age of ten, and set about spending her life fulfilling her duties as a major landowner in Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Kent. “But hold on, Julie,” I hear you cry, “this newsletter is supposed to feature the ordinary people of Oxfordshire, not the toffs.” Well, please humour me, dear readers, and you will soon see where the interaction between Upstairs and Downstairs comes in. For Sophia’s little-known mother was remarkable too, in her own way, and this article compares the bold matrimonial choices that these two women made in the terms of the society in which they moved. This feature is based on an article which first appeared in the Oxfordshire Local History Journal1, so be warned: the style is somewhat academic. We’ll start with Sophia’s mother, and move on to Sophia’s tale in part 2.

Swalcliffe Park near Banbury

THE WYKHAMS HAD BEEN at Swalcliffe Park near Banbury since the thirteenth century; they chose not to deny flattering but unfounded rumours crediting the family with descent from William Wykeham, the fourteenth-century bishop of Winchester, a prominent statesman under Edward III, Richard II and Henry IV.2 But they were not so grand as to eschew the opportunity of defraying the considerable outgoings of a property like Swalcliffe by letting it out to tenants where possible. In 1789 these tenants were the Wrightsons of Yorkshire, and a somewhat startling domestic upset below stairs yields for historians two examples of matrimonial choices where the parties consciously flouted the social norms of the day.

From 1784 to 1789, Yorkshire landowner William Wrightson of Cusworth, MP for Aylesbury, and his wife Henrietta took the property, perhaps for the duration of the parliamentary terms. A romantic entanglement involving a member of the Wrightson household staff suggests that the Swalcliffe heir, William Richard Wykham (1769–1800)3 , had not removed very far during his retirement from the main house. Young men have ever been known to hang about hopefully in the nearest kitchen, and an attachment had formed between William and Henrietta Wrightson's cook. On 8 March 1789, Mrs Wrightson wrote to her sister Mary with delicious news:

“A very pretty woman”

"Our cook, you must know (who, indeed, I always thought a Very pretty woman) has long been the 'Dulcina de Tobozo'4 of Mr. Wykham, & his declarations of its being his intention to marry her have for some time past been Well known in this County. As she was too prudent to listen to his addresses on any other terms, & indeed I don't know that any other were proposed, last Week he inform'd her of his intention to be married tomorrow & gain'd her consent to accompany him to Town this morning. A Post Chaise was therefore order'd to stop a few fields distant from the House at 6 O'clock, at wch time they met & decamped together.

"… I am not a little anxious for the Young Woman, Who has always appear'd perfectly modest & well dispos'd – & indeed as a Servant I have every reason to speak well of her. Nor am I particularly Obliged to Mr Wykham for running off with her to-Day, as I happen to expect a party of Gentlemen at Dinner from Honington – &, being at present without a House-keeper, have only the Kitchen-maid to dress the Dinner. But when a Lady has had her Cook run away with, it is certainly Apology sufficient to her guests."5

"Young" the runaway bride most certainly was not – in fact, she was thirty-seven – but William Richard Wykham definitely was; at nineteen, he was around half his intended wife's age.6 Mrs Wrightson reports that the bride had "long been" the idol of the teenaged William, and he was still under the legal age of consent.

Elizabeth Marsh hailed from Upholland in Lancashire. She was the daughter of William Marsh, husbandman – a rank hovering somewhere below a yeoman farmer. Evidently, as the end of the Wrightson's tenure at Swalcliffe approached, the couple had decided to take steps to pre-empt the inevitable complication of Elizabeth's return into the North.

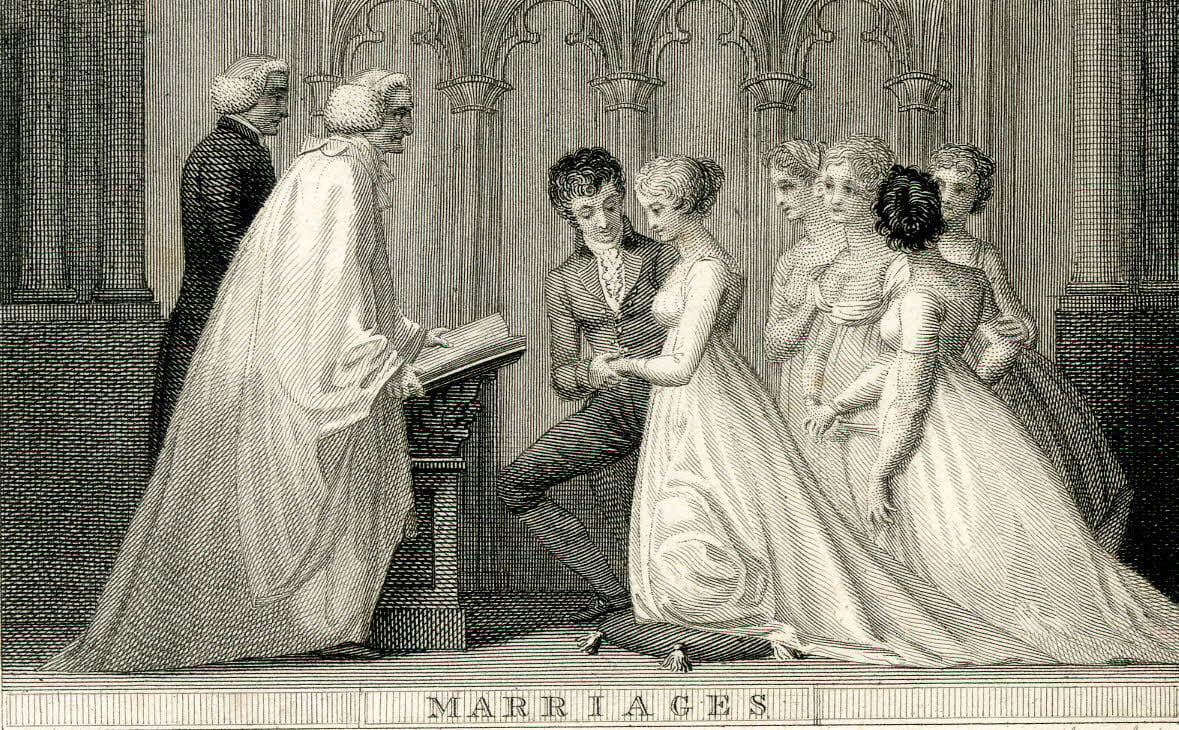

The squire married the cook in 1789

Even in the apparently transgressive circumstances of a marriage that crossed class and age boundaries, there appears to have been little or no attempt at concealment. The banns were read on 21 and 28 June and 12 July,7 and the ceremony took place in the church at the neighbouring village of Tadmarton on 16 July 17898 . The groom's mother, who was still living in 1789, seems to have expressed no objection to the match (if, indeed, she was given the chance to do so). Mrs Wrightson was obliged to return to Yorkshire minus her excellent cook.

Henrietta Wrightson's assertion that she was "not a little anxious" for Elizabeth Marsh suggests that she did not regard such arrangements as necessarily always ending happily. But once the marriage was solemnised, there was very probably a resignation to a fait accompli involving a young squire. We are informed these days that our Prince of Wales's friends are politeness itself to his mother-in-law Mrs Middleton, a former air stewardess, but this does not apparently preclude jokes about "Doors to Manual" circulating among his companions. By definition, such stories can never be verified outside the social circle most directly concerned, but a strategy of distancing oneself from of a member of an inferior class by means of quiet mockery, twinned with outward acceptance of a decision by a member of the élite, would seem to be a pragmatic way forward in society.

In October 1790, Elizabeth Wykham gave birth to Sophia.9 Doubtless Wykham and his wife were delighted with their healthy baby girl, but Elizabeth's age meant that the provision of a male heir for Swalcliffe was becoming urgent. Ten months later a son, William, was baptised on 1 August 1791,10 and Elizabeth died a week later.11 Two pregnancies in such quick succession seem to have been too much for the constitution of a forty year-old woman, who would at that time have been considered well into middle age. Elizabeth's early demise deprives historians of material upon which to judge the extent to which society would accept a marriage which contravened social norms.12 The little boy died in November 1798, aged seven.13

Two years after his son's death, William Richard Wykham inherited Thame Park. This was because his own father had married the Honourable Sophia Wenman, sister of the seventh Viscount Wenman. Viscount Wenman was the last of his line, so Thame Park descended upon his death in March 1800 via his sister to his sister's son William Richard Wykham. Barely had William Richard had time to advertise for let the enormous house at Thame Park14 than everything changed again, and his daughter Sophia would become one of the richest heiresses in the land, in a position to marry any bachelor she liked.

Find out how Sophia’s approach to marriage was affected by her parents’ irregular liaison in “The squire, the cook, their daughter and the Duke: part 2”, coming up soon.

1 Oxfordshire Local History Journal, vol 11, pp 27–37.

2 Bishop Wykeham is now thought to have been born born William Longe, the son of John Longe, a freeman from Wickham in Hampshire. See Partner, Peter, 'Wykeham, William (c. 1324–1404)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

3 Some sources give Wykham's death date as 1805, but the monument in the church of St Peter and St Paul, Swalcliffe, shows a date of 1 July 1800.

4 A character in Don Quixote.

5 Bamford, Francis (ed.), Dear Miss Heber: An Eighteenth Century Correspondence, Constable, London, 1936. Letter number 19. Original punctuation and capitalisation.

6 Drl/2/522, Bishop's Transcripts, Wigan, 24 November 1751.

7 OHC PAR262/1/R1/3 Swalcliffe parish register, 21 October 1769.

8 OHC PAR268/1/R3/1, Swalcliffe parish register, 12 July 1789.

9 OHC PAR262/1/R1/3, Swalcliffe parish register, 6 October 1790.

10 OHC PAR262/1/R1/3, Swalcliffe parish register, 1 August 1791.

11 OHC PAR262/1/R1/3, Swalcliffe parish register, 8 August 1791.

12 However, see the author's book, The Water Gypsy: how a Thames Fishergirl became a Viscountess (2016) which tells the tale of a contemporary Oxfordshire marriage across the social barrier, and the ramifications of the bride, a fisherman's daughter, Lady Elizabeth Ashbrook being widowed at an early age.

13 OHC PAR262/1/R1/3, Swalcliffe parish register, 10 November 1798.

14 Jackson's Oxford Journal, 10 May 1800.