- Forgotten Lives of Oxfordshire

- Posts

- The prisoner problem

The prisoner problem

by Julie Ann Godson

Just like today, Regency Britain lacked sufficient accommodation to imprison convicted criminals for extended periods, so judges could only impose punishments which we view today as either extremely lenient or ridiculously harsh: a couple of months’ in clink for child abuse, death for stealing a horse. The facilities for anything else simply did not exist. But once the French showed signs of sniffing round the continent of Australia, an alarmed establishment came up with a wheeze designed to kill two birds with one stone – exporting fit young wrong-doers to the other side of the world to establish Britain’s suzerainty over a new colony. For the ordinary men and women of Oxfordshire, being sentenced to transportation must have felt like being sent to the moon, never to see your loved ones again.

Lower Heyford, with the Bell Inn on the right

Not many prisoners in Georgian England insisted on pleading guilty to an offence carrying the death penalty – especially when they have already escaped hanging once before. In 1815, at the age of 31, Thomas Bunce had been found guilty of stealing a brown mare from Thomas Dorr of Finstock and sentenced to death.1 Horse theft was regarded as a serious crime at the time, and the statutory penalty was execution. But the final decision to commute a sentence to transportation or imprisonment rested with the 'hanging cabinet' (or Grand Cabinet), a senior group of government ministers under the authority of the monarch and directed by the Home Secretary or Prime Minister.2 This group would then assemble in the presence of the reigning monarch and review a list of 'Capital Convicts’.3 Thomas was reprieved. He served five years aboard the prison hulk Leviathan.

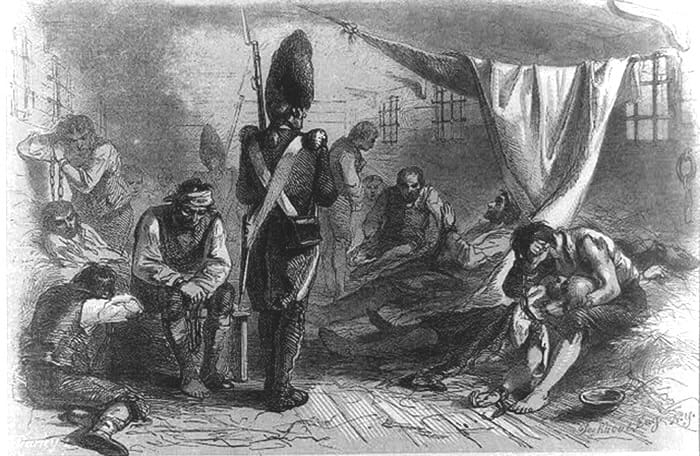

Conditions on board the hulks were insanitary and inhuman

Conditions aboard the Leviathan hulk at Portsmouth in the 1820s were designed to strip convicts of whatever dignity they retained and subdue them into the system. The prisoners were taken aboard and ‘paraded on the quarter-deck of the desecrated old hooker, mustered and received by the captain. Their prison irons were then removed and handed over to the jail officials, who departed as the convicts were taken to the forecastle. There every man was forced to strip and take a thorough bath, after which each was handed out an outfit consisting of coarse grey jacket, waistcoat and trousers, a round-crowned, broad-brimmed felt hat, and a pair of heavily nailed shoes. The hulk’s barber then got to work shaving and cropping the polls of every mother’s son.’ Fettered and shaven prisoners were then marched below ‘where they were greeted with roars of ironic welcome from the convicts already incarcerated there’.4

After evading a sentence of death and surviving for five years on a prison hulk, one might imagine that Thomas Bunce would appreciate his narrow escape and keep his nose clean. But he was back in court in 1823, this time for stealing four pigs worth eight pounds from the barn of Joseph Grantham at Lower Heyford. Bunce insisted on pleading guilty; he was a widower, so perhaps he didn’t care what happened to him.5 But the public was becoming uneasy about the number of hangings. Thomas was sentenced to seven years’ transportation.6 In April 1824 convict ship Chapman departed for Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) carrying 180 male convicts; she arrived at the end of July.7

Convict ship Chapman

Upon arrival, as an agricultural worker, Thomas would have been assigned to an appropriate position with an employer on a farm or a sheep station. The name “Strahan” given on the record of Thomas’s conduct during his servitude suggests the possibility that his master may have been farmer Robert Strahan of Bonnington, Hollow Tree, Clarence Plains.8 An entry alongside Thomas’s name states: “July 7 1828. Strahan/Absented himself from his Master’s service.” The next entry reads: “Jun 2 1832. F. S./Charged on the information of W De Gillern9 with stripping on 20 May a number of mimosa trees growing upon his land of their bark.” Evidently Bunce had been moved to de Gillern’s property. According to historian Peter MacFie, former Prussian army officer William de Gillern appears to have been a poor manager of his assigned servants, who continually used disruptive tactics to impede his farming operations.10

Major William de Gillern of Glanayr: not a popular man with his servants

During the seven years of his sentence Bunce was not free to work on his own account or to return to England. But once his sentence was up he was considered “free by servitude”; he could support himself as he pleased. If a prisoner did want to return to England, he had to pay his own way or work his passage. Most had started families by then and this, along with an abundance of work, food, and sunshine, generally pursuaded them to stay put.

A seven-year sentence commencing in 1823 would expire in 1830. In 1837 one Thomas Bunce was working as a “free hired servant” for wealthy merchant Samuel Terry11 in Bathurst, New Brunswick, two hundred kilometres inland from Sydney.12 We know this because he was in court for drawing a pound on account and “hiring himself” to proceed to Bathurst, but then he absconded and hired himself out to another party on the Parramatta Road. So is this our Thomas Bunce? The fact that Sydney was only a few days by sea from Van Dieman’s Land, and that labour had to be supremely mobile in a developing country makes it eminently possible. One interpretation is that Bunce arrived in Sydney, collected the pound wired thence by Terry to fund his journey to Bathurst, then spent it on travelling to a different employer on the Parramatta Road. A foot in the door on the Terry property would have been a good opportunity; it would be typical of Bunce (and many, many other convicts) not to realise when they were well off. He was jailed for a month.

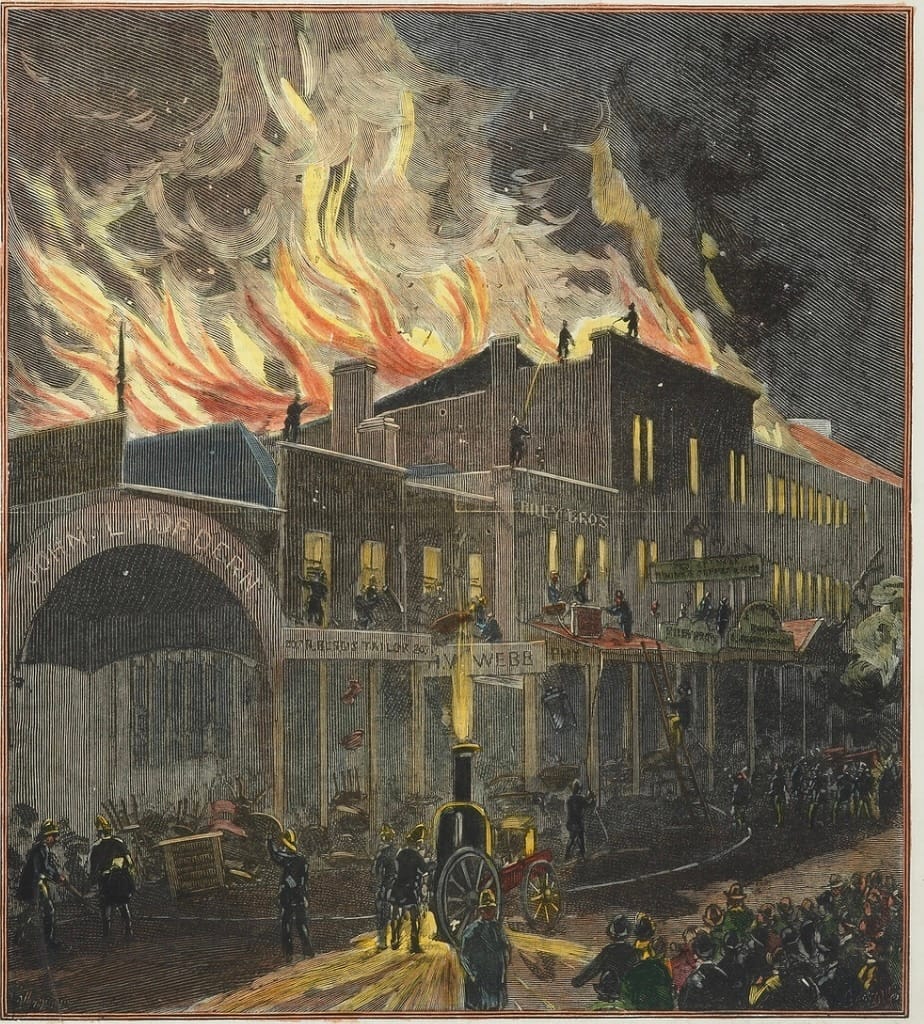

Fire at the Victoria Theatre in Sydney: this time in 1880

By the time Bunce set fire to the Victoria Theatre in Sydney in 1844, he had already worked there as a carpenter.13 This would fit well with the pattern previously exhibited by Bunce of working in a job for a few years, and then moving on. This job, too, seems to have ended badly; at 7pm on a Wednesday evening smoke and flames were observed issuing from the theatre in Pitt Street, and a “notoriously bad character named Thomas Bunce” was apprehended. In a storage room a number of “stuffed horses” known to have been made by Bunce were ablaze, along with other theatrical props. However, the only evidence against Bunce was his own statement that he knew the identity of the incendiary.14 He claimed that the new manager Simes had previously received a ten pound reward for extinguishing a fire at the theatre, so he hoped to achieve the same result again. However, it also emerged that Bunce had been dismissed by Simes. Thomas was committed for trial, whereupon he bailed himself in the sum of £80 and two sureties each of £40 and disappeared.15

A puzzling newspaper announcement in 1856 appealed for information respecting the whereabouts of a “Thomas Bunce”:

INFORMATION is required respecting THOMAS BUNCE, alias THOMAS THOMPSON, who is said to have carried on business as a wholesale butcher in Market-street, Sydney. He arrived in the colony about 1828, and is reported, in England, as having died in 1842. The date of his death and other particulars are desired. Any parties who can give the information will greatly oblige the advertisers, by addressing SPICER BROTHERS, Herald Office.16

The fact that this Bunce sometimes used the alias “Thomas Thompson”, just as in England three decades before our Thomas had used “Thomas Turner”, strengthens the suspicion that it is the same man.17 Whilst a search in the relevant records reveals only a handful of Bunces (and only one Thomas), there are many Thomas Thompsons – several with good reason to keep a low profile. Tracing the histories of all of them seems likely to prove an unprofitable use of time.

In the following year the name “Thomas Bunce” was also included in a newspaper column entitled “Missing Friends”.18 It was very easy to lose touch with family members in such a fluid society where labourers were often moved from place to place as required. Letters coming from England might easily be addressed to places that the intended recipient had already left. And, of course, using such a facility to seek information on a man who had jumped bail would seem entirely reasonable.

Woodend, Victoria

Perhaps we know where Thomas was. Sometime between 1844 and 1853 he retreated to Van Dieman’s Land. Then in February 1853 he took a ship from Launceston to Melbourne.19 When he next appeared in the record in 1860, he was working as a “carrier on the road” in the small town of Woodend, some eighty kilometres north east of Melbourne.20 Once again he was connected to a case of arson, but this time as an innocent bystander. Described in court as “a very old man” and “very deaf” (our convict would have been 77 years old), Bunce appears to have been part of a set-up by local resident Mary Ann Rennie to lure the suspected arsonist to her house in order to have him confess aloud his crime before a witness. Thomas deposed in court that, on the night of the prisoner’s visit to Mrs Rennie’s house he overheard a portion of the conversation. He heard the prisoner say something about three pounds, to which Mrs Rennie replied, “Is that all?… Did you hear that, Tommy?” Thomas replied that he did.

After this, once again Thomas disappeared – this time for a full twenty years. A sad report in the New South Wales Police Gazette in 1880 reveals that one Thomas Bunce had been charged by Walcha and Armidale Police (some five hundred kilometres north of Sydney) with being of unsound mind. It was ordered that he should be sent to Gladesville Asylum in Sydney.21 Thomas Bunce, originally of Lower Heyford, would have been 97.22

Gladesville Asylum in Sydney

Tracing the outcomes for Oxfordshire convicts in their new lives on the other side of the world can reveal whether they were, say, hapless but good-hearted men trying to feed their families by means of a bit of poaching, or confirmed ne’er-do-wells who would be trouble wherever they went. Of course, even the innocent (perhaps especially the innocent) may have been embittered by the harshness of their treatment, and felt they may as well kick back at apparently indifferent authorities ruling their lives. But many convicts, given the opportunity to work, build a home, and start a family, acquitted themselves well, rising to respectable positions in society. I think it would be fair to say that, even if our Thomas Bunce was not responsible for every single deviation from the law catalogued here, he was probably destined to be a lifelong nuisance, whichever continent he was on.

1 Oxford University and City Herald, 11 March 1815

2 Bryant, Chris, James and John, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2004, p. 193–195.

3 Ibid, p. 205-206.

4 Tucker, J., (‘Giacomo Rosenberg’), The Adventures of Ralph Rashleigh: A Penal Exile in Australia, 1825-1844.First published in 1929, though thought to have been written in the 1840s.

5 https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON31-1-1/CON31-1-1P292 [accessed 6 Nov 2025]

6 Oxford Journal, 12 July 1823

7 https://convictrecords.com.au/convicts/bunce/thomas/109952 [accessed 6 Nov 2025]

8 https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON31-1-1/CON31-1-1P292 [accessed 6 Nov 2025]

9 Major William de Gillern of Glenayr, Grass Tree Hill Road, Richmond

10 https://petermacfiehistorian.net.au/wp-content/uploads/A-SOCIAL-HISTORY-OF-RICHMOND-4.pdf [accessed 6 Nov 2025]

11 Known as the “Rothschild of Sydney”. Sydney Times, Mon 26 Feb 1838

12 Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Sat 4 Feb 1837

13 Weekly Register of Politics, Facts and General Literature, 28 Sept 1844

14 The Australian, 30 Sept 1844

15 Weekly Register of Politics, Facts and General Literature, 28 Sept 1844

16 Sydney Morning Herald, Sat 3 May 1856

17 Oxford Journal, 12 July 1823

18 Sydney Morning Herald, 6 January 1857

19 https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/POL220-1-3/POL220-1-3P038

20 The Age, 17 Apr 1860

21 New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime, 7 Apr 1880

22 Oxfordshire, England, Church of England Baptism, Marriages, and Burials, 1538-1812, Anglican Parish Registers; Reference Number: PAR131/1/R1/1, Baptisms, Lower Heyford, 16 Feb 1783