- Forgotten Lives of Oxfordshire

- Posts

- The little chimney sweep

The little chimney sweep

by Julie Ann Godson

Boy sweeps might die at work, or from the harmful effects on their health

Children were widely used as human chimney brushes in England for about two hundred years. The ideal age for a child sweep to begin working was said to be six years old, but sometimes they started at age four. They were required to crawl through chimneys about eighteen inches wide; the child would shimmy up the flue using his back, elbows, and knees. He would knock the soot overhead loose with a brush, and it would cascade down over him. Once the child had cleaned all the way to the top, he would slide back down and collect up the soot pile for his master, who would then sell it as fertiliser. Children often became stunted in their growth and disfigured because of the unnatural position they were required to adopt before their bones had fully developed. Their lungs would become diseased, and their eyelids were often sore and inflamed to the point where some sufferers lost their sight altogether.

IN FEBRUARY 1875, there was a national sensation when a twelve-year-old chimney sweep named George Brewster became stuck in Fulbourn hospital chimneys in Cambridgeshire.1 An entire wall was pulled down in an attempt to rescue the boy, but he died shortly afterwards. Brewster’s master was found guilty of manslaughter, and a bill was pushed through parliament in September 1875 which was designed to put an end to the practice of using children as chimney sweeps in England. But it did not, and rival sweeps lost no opportunity to inform on one another – not out of compassion for the children but because of the financial advantage a rival derived from paying children’s wages.

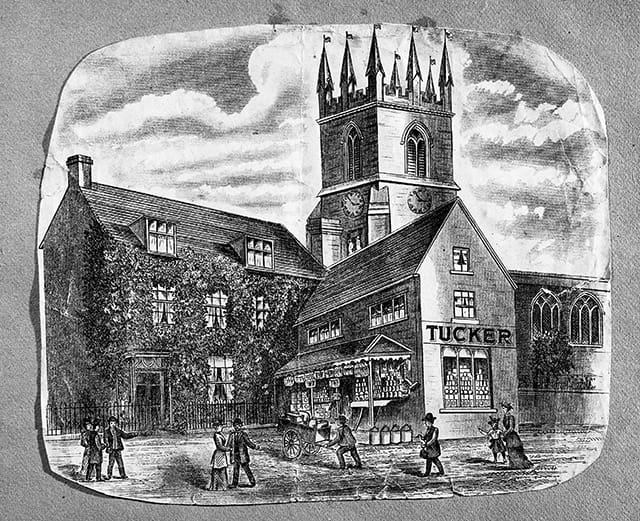

Deddington marketplace [www.deddingtonhistory.uk]

In December 1880, a small boy was seen crying in the street in Deddington, struggling along with a chimney brush far bigger than he was, his clothes black with filth. When asked why he was upset, little Alfred Edwin Yerbury, 9, told Inspector Wyatt that he did not like chimney work.2 Rival sweep Thomas Evans from Neithrop3 immediately intervened to point out that Yerbury’s master, Charles Dixon, was in breach of the law in employing a child under ten. Today we give a cheer for Thomas Evans, and cast Dixon as a wicked exploiter. However, rather than congratulating ourselves on our own moral superiority, we should perhaps look more carefully at a time of transition in society.

Little Edwin, as he was known in the family, was actually the grandson of Dixon's wife Elizabeth from her first marriage to another sweep, Henry Jarvis. He was born in 1871 at the Dixon home near The Windmill south of the Hempton Road out of Deddington.4 The windmill itself was demolished around 1840, and a group of lowly cottages housing mainly paupers was crammed on to the site. Within weeks of Edwin's birth, his father John Yerbury, a painter and decorator, had cleared off back to his parents' home in Birmingham.5 He reunited with Edwin's mother Mary Ann only long enough to conceive a daughter, Elizabeth, born in 1873,6 but thereafter there were no more children, suggesting that John had departed the domestic scene for good. Back in Deddington in 1880, Charles Dixon claimed that the sobbing little boy was merely conducting his assistant, George Gardner, to properties requiring his services while he himself was indisposed. The magistrates did not believe this and fined Dixon one pound plus ten shillings costs.

Like so many Victorian children, this unhappy boy sweep on the left is barefoot

But before we condemn Dixon too roundly for child-exploitation, it is worth examining his background and circumstances too. Charles Dixon grew up in a family of sweeps in Chipping Norton; the Dixon clan was extensive and individuals are difficult to pin down for certain, but Charles was born to father Joseph in 1825, and a Joseph Dixon died when Charles was just seven years old.7 This may explain why, by 1841, Charles was living with a possible uncle, William Dixon, in Churchill Road, West End, Chipping Norton, along with William’s wife Rachael and eight other young Dixons aged between 12 and 20, some his siblings, some not. His sisters Jane and Elizabeth lived next door with the Howe family.8 The only person in the Dixon household who was not a Dixon was George Buggins who, at ten years old, was a “sweep apprentice”.

The Dixon clan of sweeps came from West End, Chipping Norton

This type of extended family household is an example of how working people mucked in together to take care of orphaned nephews and nieces. And a family of sweeps had the wherewithal to provide employment by which these children could earn their keep. It was such a commonly accepted practice that local parishes would pay the master sweeps to take on waifs and strays to teach them a trade. When this happened, they were obliged to give the child on-the-job training, a set of clothes, and have them cleaned once a week.18

For the ‘lucky’ boys, who found a way to survive for seven years, they could become a journeyman sweep (i.e., they did the same work but could choose their own master sweep) and then, perhaps, become a master sweep. Although only George Buggins is described as an apprentice sweep in the 1841 census, doubtless the other boys were going up chimneys too, even if they weren’t official apprentices. This was normality for Charles Dixon; it was what good, responsible people did for their nearest and dearest.

Altogether, three of Mrs Dixon's grandchildren lived in the cottage in Castle Street.9 At 67, she probably found a nine year-old, a seven year-old and a three year-old hard work as well as costly to feed. Edwin’s mother Mary Ann Jarvis Yerbury was obliged to go into service as housekeeper to the vicar at Weston on the Green. Perhaps it is unsurprising that Edwin was expected to earn his keep too, and the obvious employment that Charles Dixon could offer was chimney-sweeping. As we have seen, he, too, had probably worked as a boy sweep; his own son Charles had died at fifteen,10 though whether or not from working as a child sweep it is impossible to say, and his younger son, Henry Dixon, worked as a child sweep too.11

Castle Street East in Deddington – with a sweep and his cart on the left?

As it turned out, the 1891 census shows that Edwin did take up chimney sweeping for his trade.12 He married Cecily Jarvis,13 a cousin who had also grown up in the ever-accommodating Dixon household, and the couple had three children. His younger son, Alfred Edwin, died of his wounds aged nineteen on the Western Front in 1917.14 After a spell as a cook at Farnborough School in Hampshire,15 Edwin's mother Mary Ann came home to work in Deddington and never remarried. She died in 1935.16 Edwin spent the rest of his life in Castle Street and died aged 74. He was buried in Deddington churchyard on Christmas Eve in 1945.17

Very little changes overnight in society. Some of us are old enough to remember the grumbling there was at the introduction of compulsory seat-belt wearing in cars in 1983. Even today, many rural-dwellers know a neighbour who feels perfectly entitled to continue lighting a bonfire on his own land as he remembers his grandfather and great-grandfather doing. Safety benefits sometimes take a while to be accepted. Those who condemn Charles Dixon and his like must therefore suggest what he should have done with a child that needed a home, but that he could not afford to keep? Hands up for the alternative? The workhouse.

This is an expanded extract from Julie Ann's book On this day in Oxfordshire: volume 1. Her books on the history of Oxfordshire are available at Amazon.co.uk. You can follow her on Facebook at @julieanngodson.

The reminiscences of Edwin’s grandson James Yerbury give an invaluable and detailed picture of life in Deddington in the 1930s: https://www.deddingtonhistory.uk/people/indexxyz/jimyerbury

1 Western Daily Mercury, 13 February 1875

2 Banbury Guardian, 23 December 1880

3 1881 England Census, Neithrop, Oxfordshire, Thomas Evans, sweep

4 Oxfordshire, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1915, Deddington, bap 25 Dec 1878, “born Dec 9th 1872”

5 1871 England Census, Birmingham, Warks, John Yerbury, “unmarried” – although the Deddington register shows he married Mary Ann Jarvis on 3 Apr 1870

6 1891 England Census, Deddington, Oxfordshire, Elizabeth Yerbury

7 Oxfordshire, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1965, Chipping Norton, bur 1 Oct 1832, Joseph Dixon

8 1841 England Census, Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire

9 1881 England Census, Deddington, Oxfordshire, Charles Dixon

10 England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915, Woodstock Oct-Nov-Dec, Dec 1871, Charles Dixon

11 1871 England Census, Deddington, Oxfordshire, Henry Dixon

12 1891 England Census, Deddington, Oxfordshire, Alfred H E Yerbury

13 Oxfordshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1930, Deddington, 26 Dec 1892

14 British Commonwealth War Graves Registers, 1914-1918, Yerbury, Pte Alfred Edwin, 40660

15 1901 England Census, Farnborough, Hampshire, Elizabeth M Yerbury

16 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/277997653/mary-ann-yerbury

17 Oxfordshire, England, Church of England Deaths and Burials, 1813-1965, Deddington, 24 Dec 1945, Alfred Edwin Henry Jervis Yerbury