- Forgotten Lives of Oxfordshire

- Posts

- A Napoleonic officer in Thame

A Napoleonic officer in Thame

by Julie Ann Godson

Around five hundred French naval officers were held as prisoners of war in Thame during the years of the Napoleonic Wars. As officers, and therefore by definition, gentlemen, they were allowed to live reasonable freely in the town, but they were obliged to sign a bond on their honour not to attempt to escape. Pierre-Marie-Joseph (later Baron) de Bonnefoux (1782–1855) was captured on the Marengo at the age of 24 when British and French squadrons met unexpectedly in the mid-Atlantic in March 1806. He spent the next few years as a prisoner in Britain. This is an extract from his memoirs describing his impressions of Thame. (Mauvaise traduction par moi et Google.)

Thame church and the Prebendal House in 1835 [William Turner of Oxford]

“THAME IS A SMALL TOWN in Oxfordshire situated near the source of the [sic] Thame, which is but a small stream, and in a country which is about as rainy as the rest of England, but wooded, picturesque, and perfectly cultivated. We arrived there in May 1806, and it had been so long since I had enjoyed the appearance of spring that the beauty of the views seemed even greater to me.

“There were factories in this town whose workers, part of a floating population, were not linked to the area by family ties, and among whom the responsibility lay for reprehensible behaviour. This scum, upon whom newspaper reports filled with virulent imprecations against France acted powerfully, allowed its resentment towards we defenceless prisoners full rein, and rarely missed the opportunity to provoke us with insults, and then engage us in a fight with stones or hand-to-hand combat. The peaceful inhabitants of the town groaned at these shameful scenes, but they were mostly afraid of the workers. They feared being viewed as bad patriots, and it meant a lot [to us] when they refrained from approving of the troublemakers.

“Some families, however, found themselves led by particular circumstances or by pressing recommendations to maintain relations with some of us. Such were the Luptons1 and Stratfords2 , to whom I was introduced by an officer named Litner3 , a charming young man recently graduated from Saint-Cyr, with whom I had quickly become friends and who, like me, had just seen his sword broken by adverse fortune. Mr Lupton had one son and two daughters, Mr Stratford, two daughters. Sometimes, friends met at their house and, at that time, an elegant lady from London, a very great friend of the Lupton ladies, Miss Sophia Bode, was visiting them, a visit which she renewed every year.

One of the older houses in Thame High Street of the sort occupied by the Luptons

“With these pastimes, which my brothers joined in, my friends, and this company, I managed to find the time bearable, especially since these ladies were well brought up, pretty and very well educated. They wrote charming verses, Miss Jane Lupton especially. She composed some lines about a sparrow that I had tamed and which she had mischievously named Flora, after a little spaniel belonging to Miss Harriet Stratford, which died in spite of our care and concern. In the unfortunate vicissitudes of life there is, undoubtedly, no better way than to look for the good in the setbacks, and thus make them less painful. This is what I managed to achieve at Thame, but this state of affairs did not last long.

“I was returning home one day with Litner when a passing worker hit me roughly in the chest. I pushed him even harder, and he fell. He shouted. Comrades gathered. Frenchmen came running towards us and a fight ensued with stones with which I was impressive, with fists, with canes and sticks. When they managed to separate us, bruises were evident, and blood had been flowing for some time. I had not lost sight of my attacker, and I managed to drag him before Mr Smith4 , the prisoners' commissioner, from whom I demanded the man’s punishment. He promised it to me; but, after a few days, he told me that there was nothing he could do, that the matter had to go to Oxford, and he authorised me to go there to lodge a complaint with the king's attorney. I suspected that Mr Smith, fearing the resentment of the workers, was only trying to drag out the matter so that it would die on its own.

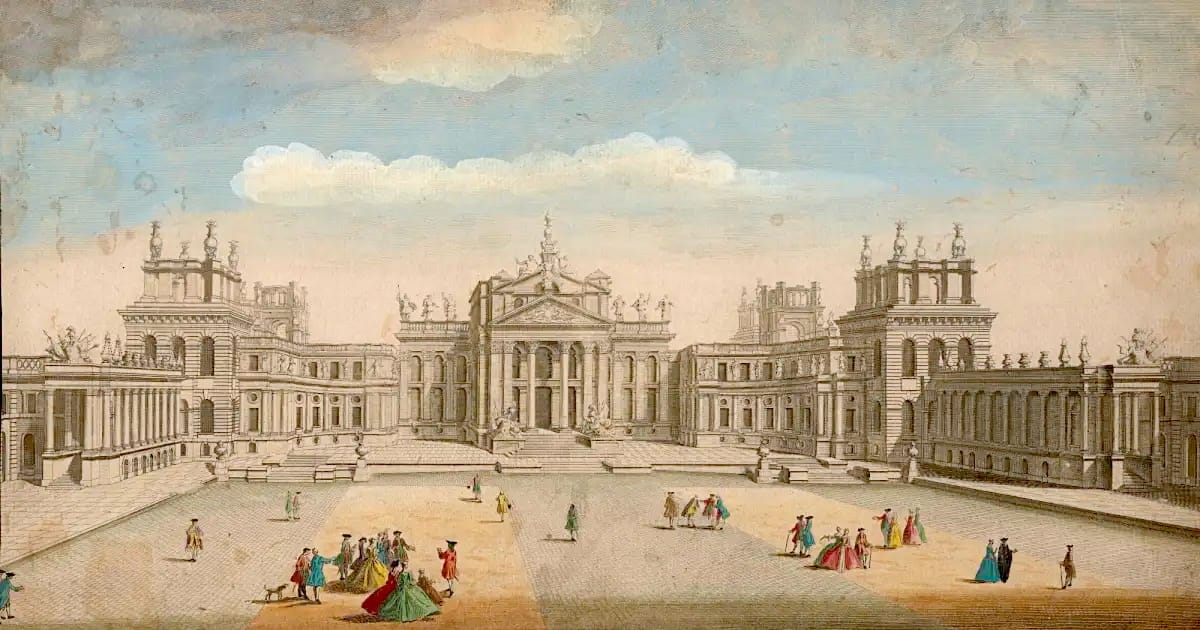

Bonnefoux visited Blenheim Palace [Engraving by James Mynde (1702–1771)]

“Even so, I eagerly seized the opportunity to see Oxford, its University, its twenty-two colleges, its beautiful walks, and Blenheim, which is nearby. Sumptuous Blenheim Palace, the prize awarded by the nation to [John] Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, Queen Anne’s general against Louis XIV and whose gigantic proportions, and magnificent park eight leagues around epitomise everything that can flatter vanity.

“The magistrate replied that he could not initiate an action between an Englishman and a prisoner of war without the authorisation of the government. This legality which, for civil matters, put us beyond the scope of common law, seemed to me quite singular in a country which claims to be so impartial. So I returned to Thame without any resolution, and pressed Mr Smith again. As his ill will could not fail to appear throughout the day, I reproached him for it. A scene ensued – he even threatened me with assault, and grabbed a cane. As quick as him, I armed myself with a poker and challenged him. His wife and his servants came running; I challenged him again in front of them. I called him miserable, and then I left, telling him that I was going to file a complaint against him through the Transport Office which, in London, is the office responsible for the service of transport ships and to which, during wartime, is added the guarding, surveillance and care of prisoners. In this complaint, which I soon delivered to Mr Smith himself so that he could send it on to Transport Office, I asked for his dismissal, and again for justice against the aggressor in the fight. Mr Smith then offered to apologise to me in his office; but I demanded the apology in the presence of ten prisoners. We could not agree, and off went my complaint.

“The response was a further act of contempt for the common law, for Mr Smith was ordered to give me a bill for another bond town called Odiham situated in Hampshire, and that if I had not departed within twenty-four hours, I should be arrested and taken to the pontoon [prison hulk]. That, at least, was plain speaking: it was Turkish, it was outright, pure despotism. We see clearly what these people mean by justice, we submit, we despise them, and we leave. That is how it is, at any rate, with England having a Machiavellian government which does not shy away from any act of bad faith when it believes it to be useful to its own interests, afflicted with a populace always ready to serve the worst passions, and in the midst of all this, accommodating men of the noblest character, soldiers of the greatest loyalty, individuals to whom no good deed is difficult [i.e. Frenchmen].

“I believe that the prisoners had encouraged me a little in all this. They rewarded me with a sort of public ovation, by leading me, en masse, to the end of the mile.”5 Here Bonnefoux parted sorrowfully from his fellow officers. “I left them all, struck to the heart at abandoning such tried friends. And I had a further cause for sadness. I don't need to explain that these were my new friend Litner, as well as the Lupton, Bode and Stratford families. I had said goodbye to them the day before, but, at the moment of departure, Litner, who had been summoned by them, gave me some souvenirs intended for me, and which he had received that very morning.

“Then, mysteriously, he added that he had, moreover, obtained from young Miss Harriet Anne, with her beautiful blue eyes, dazzling complexion, lively countenance, and divine figure, a lock of her admirable blonde hair which he placed in my hands, saying that I was a very lucky mortal, and that he would not regret leaving Thame if he could get as much from Miss Sophia.6 This affected me more than I expected and my departure was, in reality, just as well, because I could not, in all sanity, think of getting married at that moment. There should have been no other way out of this nascent passion, if I had continued to stay close to the one who had kindled it, and who seemed to share it.”

Bonnefoux transferred to Odiham where he exceeded his one-mile bond limit while out for a walk. He was despatched to the prison hulk Bahama where he endured twenty months under a severe regime at some cost to his health. He was then moved to Litchfield and stayed there for three years. Finally, he was exchanged for a French captain, and he landed in Boulogne in November 1811. There he learned that he had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant on 11 July of the same year. But his naval career never recovered. He respected his bail bond and declined to take up arms again, serving in peacetime on a variety of frigates and schooners. He also wrote instruction manuals for young naval recruits as well as language dictionaries. He died in Paris in 1855.

You can read Baron Bonnefoux’s memoirs in full at https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/38734

All my books are available from Amazon.

1 For several generations doctors in Thame.

2 Reverend William Stratford was master of Lord Williams’s school in Thame.

3 Ferdinand Leitner, a lieutenant in the 51st Light Infantry.

4 The unpopular agent commissioned by the Transport Office, the government department overseeing French prisoners.

5 Prisoners were allowed free movement within a one mile radius of the town centre.

6 Sophia Bode never married; she died in Southampton in 1851, aged 69. (Dorset County Chronicle, 05 June 1851.)